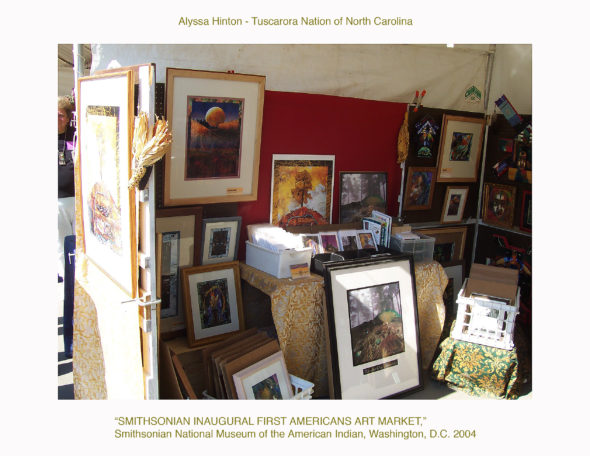

My First NMAI Event-NMAI Inauguration

2004 marked the inauguration of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, the first museum of its kind to house soley Native American art and to be coordinated and put together by Native American people, an event long overdue. I was fortunate enough to be one of (approx.) 80 artists invited to sell wares at the N.M.A.I . Inauguration. While there, I also had the chance to march with my contingent (Tuscarora/Lumbee tribal members from N. Carolina and others shown in the portrait collage below) in the procession of Indian Nations from all over the continent and beyond. This was a truly meaningful week for us, as over one million people flowed down “The Mall” in Washington, DC. Below the imagery is the USA Today article “Indian Culture Comes Home”. I hope you will read it to get a sense of just how significant the opening of this museum really was.

“Indian Culture Comes Home”

By Maria Puente, USA TODAY, September 9, 2004

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Over the past 500 years, the indigenous peoples of the Americas have been invaded, conquered, converted, enslaved, diseased, robbed, removed, confined, massacred and/or assimilated to the brink of extinction. Now, at last, they’re about to be officially celebrated here on the National Mall, with a museum they had to fight for and a story they get to tell. (Photo gallery: National Museum of the American Indian, inside and out)

Museum director Richard West says the building’s location on the National Mall “comes as close to pure historical poetry as I could ever imagine.”

There will be some mixed feelings when the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian opens Sept. 21 with six days of festivities. As many as 20,000 Indians in traditional regalia from all over the Americas, from the Arctic Circle to Patagonia, are expected to march in procession – the largest multitribal, multinational gathering of Indian people ever in history. There will be speeches and storytelling, religious ceremonies and cultural exhibits, food, music and dance, and floods of tears.

Joyful tears to be sure, but tears of mourning, too, for all who died in the centuries-long Indian holocaust. And tears of regret that it took so long to get to this point: The United States is the last major country in the hemisphere to build a national museum focused on the art, history and culture of the peoples who were here before the European conquest.

“It’s going to be pretty emotional,” says Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne), a longtime Indian rights activist and one of the “mothers” of the new museum who helped conceive it nearly 40 years ago. “We’ll be there to celebrate our survival and to commemorate our tremendous losses. … All of us will be surrounded by all sorts of relatives in spirit.”

The museum opens 15 years after it was authorized by Congress in a long fight over Indian rights legislation. It comes decades after other groups already have secured a place on or near the Mall: There’s already a museum for African art and culture, two for European art, two for Asian art, one on American history and one on the Jewish Holocaust.

Richard West (Southern Cheyenne), director of the new museum, acknowledges that a Native presence should have been first on the Mall, not last. So why wasn’t it?

“There was a tremendous cultural invisibility about Indians,” West says. On the other hand, he says, the museum occupies a symbolically important “keystone” spot, at the foot of the Capitol across from the “apotheosis of Western civilization” – the East Wing of the National Gallery.

“It’s a placement between equals in the political and cultural heart of America,” West says. Now that the country has moved toward respect of Indians, he says, the museum can help “create the groundwork for reconciliation” between Native and non-Native peoples. “It comes as close to pure historical poetry as I could ever imagine.”

Where: Independence Ave and 4th St., S.W., Washington, D.C.

Opens: Sept. 21

Hours: 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m. daily; closed Dec. 25

Admission: Free. Timed-entry passes required, available same day at museum or in advance (for a fee) through tickets.com or 866-400-6624.

Information: 202-633-1000 or www.nmai.si.edu.

10,000 years on display

It’s accompanied by architectural poetry, too: The museum’s $219 million five-story building – with 7,500 objects covering 10,000 years on display and at least 4 million visitors a year expected – is a splendid departure from the neoclassical grandeur and modernist sensibility of other buildings on the Mall. Thanks to the principle Canadian architect, Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), there are few straight lines. It’s all sinuous curves and circles, clad in textured Kasota limestone of a striking golden hue, mimicking the appearance of a timeworn Western cliff at sunset. “A post-modern cliff dwelling,” Indian Country Today, the national Indian newsweekly, called it.

Innumerable consultations with Indians led to such unique features as a main entrance that faces east, as Indian dwellings do; an outdoor offerings space for religious ceremonies; and a 120-foot-high dome that echoes the classical dome of the National Gallery across the Mall – and that will allow the mapping of the solstices and equinoxes on the circular floor below.

“As a national icon, the building should appear like a natural element,” says Duane Blue Spruce (Laguna, San Juan Pueblo), an architect and the facilities planning coordinator for the museum. “It speaks to the long history of Native peoples on the land.”

But it’s the content that counts, and on this point the Smithsonian promises a different kind of museum, one in which the “content” gets to speak. This is a departure for the museum world in general, and the Smithsonian in particular: Many Indians in the USA have long believed the Smithsonian hoards their ancestors’ bones and artifacts while treating living people as government property or anthropological curiosities. There are lingering tensions over Indian demands to return more remains and sacred objects still in the Smithsonian’s natural history collections.

“The promise of this museum is that it’s not going to be just about Native people in the past tense, but in the present and future tenses,” Harjo says.

Ceremonial cup: Inca-painted wooden jaguar qero from Peru, A.D. 1550-1800.

Artifacts with tales to tell

For the three opening exhibits, 24 Native communities selected their own objects to be displayed. They interpreted the ideas and philosophies behind the objects’ creation and use. And they tell the stories of what has happened to them as individuals and communities. Other Indian communities will be tapped on a rotating basis to do the same in future exhibits.

“We were very much impressed,” says Vivian Juan-Saunders, chairwoman of the Tohono O’odham Nation of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, one of the first 24 tribes to be spotlighted in the museum. “They came out four or five times to get the people’s perspectives on our history rather than what others have written about us. It was a different approach.”

Sad numbers

The Indian holocaust will not be ignored in the museum, but it will not dominate, either. In 1490, there were an estimated 75 million people in the Western Hemisphere; within 150 years, there were maybe 6 million Indians left. By 1900 in the USA, there were just 250,000; today, the Census reports 4.1 million Americans claim Indian heritage. Still, the 500 years since Columbus are just a fraction of the time Indians have lived in this hemisphere, so the museum can’t be just about death and destruction, West says.

For many non-Indians, much of what they will find inside the museum will come as a revelation – and will take their breath away. The museum’s collection of 800,000 objects is one of the world’s largest and best assemblages of indigenous art and artifacts. The core was acquired in the early 20th century by a wealthy New Yorker, George Gustav Heye, who traveled the hemisphere buying everything he could find, including carved masks from the Northwest coast, painted hides and feather bonnets from the Plains, and pottery and basketry from the Southwest. About 30% of the collection is from outside the USA, representing the major indigenous cultures of Canada, Mexico and Central and South America.

“What I want (visitors) to understand is the complexity, layering and richness of the Native presence,” West says.

Admiration and dissent

This richness will help Americans better understand their own land, says Tim Johnson (Mohawk), executive editor of Indian Country Today. “It’s going to serve as a great educational resource that hopefully will lead to more people engaging American Indians in their own parts of America,” he says.

There have been few dissenting voices. Bob Haozous (Chiricahua Apache), an acclaimed artist, fears the museum will emphasize “pretty pictures” at the expense of less attractive aspects of Indian life, such as racism, poverty, health problems, unemployment and lack of education. He believes the museum continues an “assimilationist” approach to Indians.

“It’s removing the philosophical element of our culture and focusing only on the decorative elements,” Haozous says from his home in Santa Fe. “It’s glorifying mankind to be dominant over nature, which is totally contrary to everything in my tribe. It’s assimilation based on the notion that Native culture is a thing of the past.”

But this view is not widespread in Indian country, say those who live there. Instead, there is a sense of optimism and hope.

After all, “it wasn’t that long ago that I would visit the East Coast and people would say to me, ‘You look like an Indian; I thought you were all dead,’ ” says John Echo-Hawk (Pawnee), director of the Colorado-based Native American Rights Fund.

Few people are likely to make that mistake from now on.